In the lush farmland of Kampong Thom province, about 3 hours north of Phnom Penh, children finish a lesson in the colourful 1st-grade classroom of a rural primary school. They are a bit more giddy than usual, in awe at the visitors who have just arrived to visit Chantha*, Damnok Toek’s first successful case of family reintegration from its Small Group Home (SGH) program.

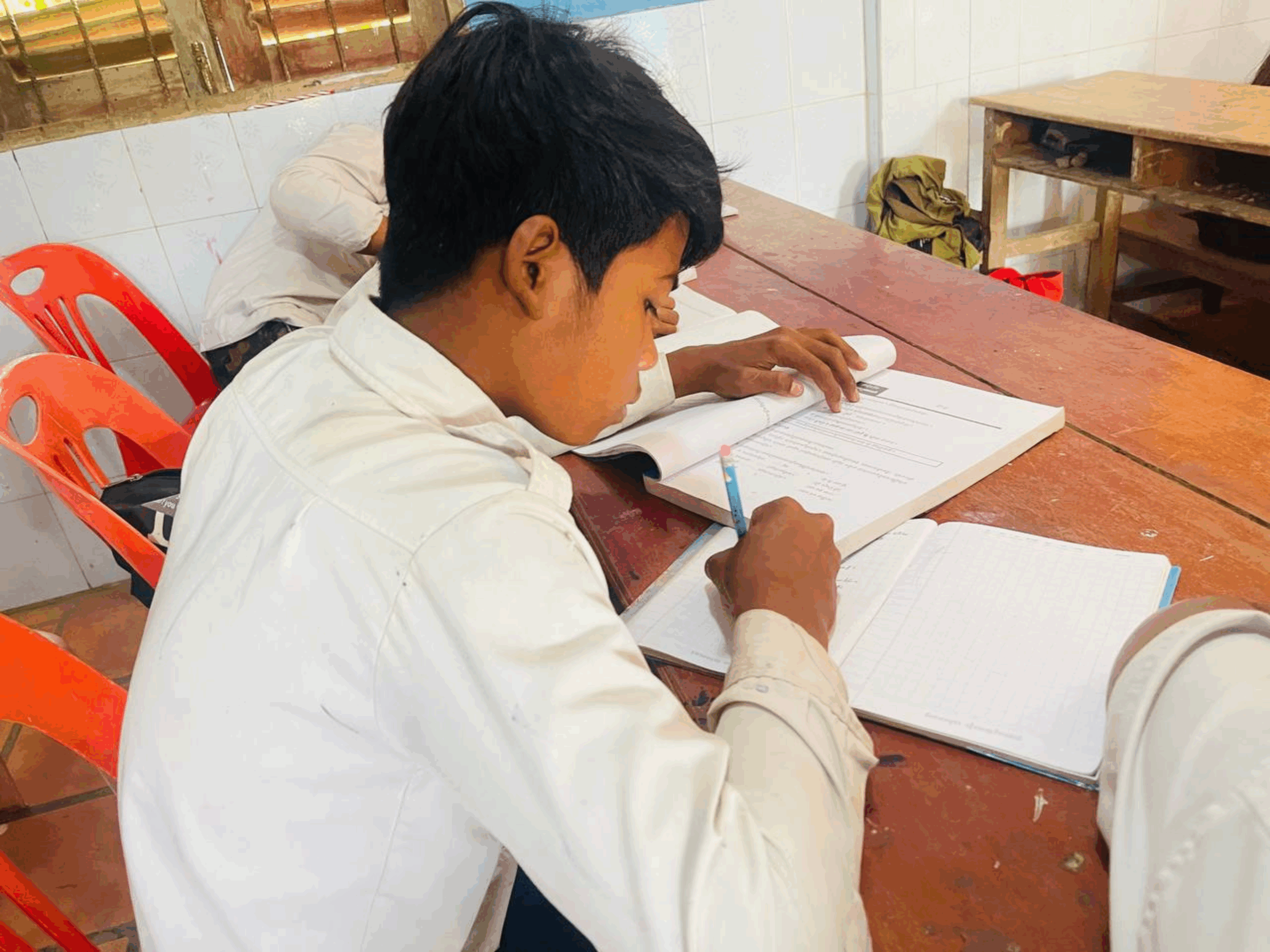

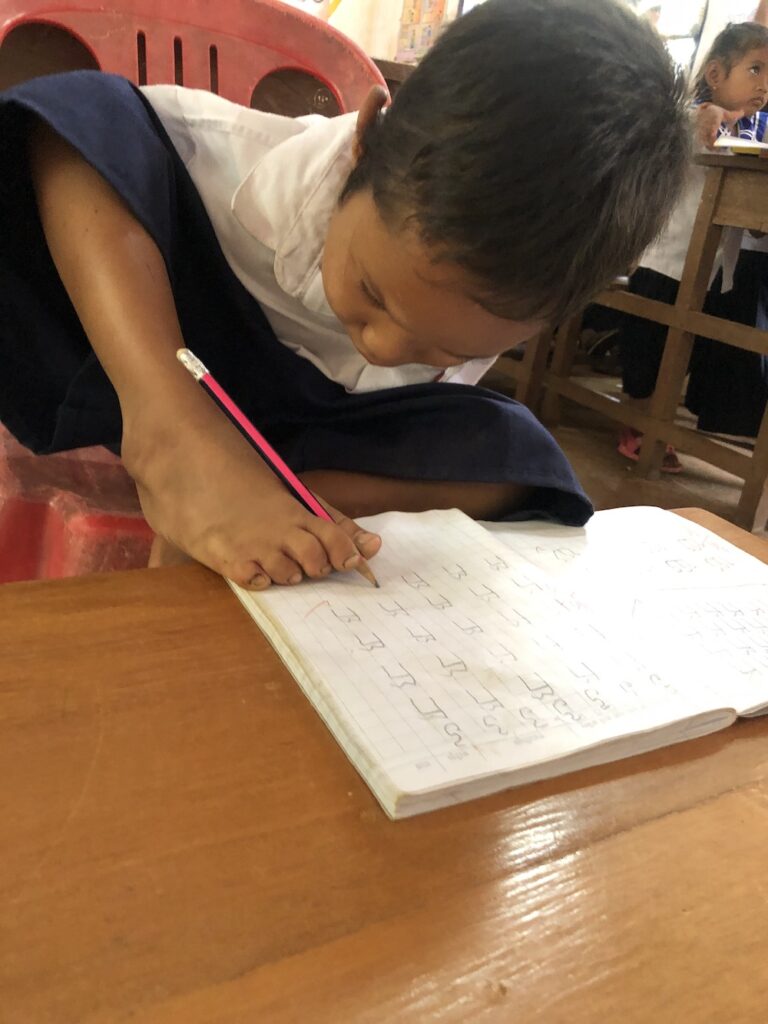

Chantha sits in the front row of the classroom, attentive to the lesson and far less distracted than his classmates are to the guests in the room. He tactfully and effortlessly uses his feet to retrieve his pencil case from his backpack, pulls out a pencil, and continues to add to his worksheet of meticulously crafted letters.

Overcoming The Odds

Chantha was born with a birth defect resulting in shrunken or deformed limbs. In Chantha’s case, he was born missing both of his arms and one of the bones of his left leg. Doctors told his mother at birth that he wouldn’t survive. Unaware of how to properly care for a child with disabilities and overwhelmed by the prognosis, she left him at the hospital. Unable to locate any of his other family, the hospital staff referred Chantha to Damnok Toek’s SGH program.

The SGH program is a specific form of Alternative Care for children with disabilities (CWD) who have experienced abuse or abandonment by their family and who currently have no other option for kinship or foster care. DT currently operates three SGHs, which are staffed by 18 caregivers who are specially trained to act as parent figures for the children in the SGHs.

Chantha progressed rapidly at the SGHs in the care of DT’s parent figures. He was taught to be self-sufficient and learned to use his legs and feet to complete all of the tasks he would have used his arms for. As an intelligent and charismatic child, he impressed his parent figures with his wit and capabilities and quickly developed the confidence to interact with and thrive around children without disabilities, especially those in his Non-Formal Education classes.

Chantha was indeed thriving in the SGH program; however, DT social workers continued to perform family tracing in the hopes of finding family members who would be willing and able to take Chantha back into their care. DT believes that a loving family environment is always the best option for children and that Alternative Care programs, including the SGH, should be used as an absolute last resort, ideally, one that is temporary until familial or kinship care can be re-established for children.

DT uses its extensive network of NGOs and partner organizations working in the field of child protection and Alternative Care to help facilitate family reintegration. This network is essential in the efforts of family tracing as organizations working in different locations throughout Cambodia communicate and coordinate to provide services and solutions to the needs of children. Therefore, DT social workers were ecstatic when they received a call from the staff at Mith Samlanh saying they had finally located Chantha’s biological grandparents.

Family Reintegration Begins

Leap* is 46 years old, tanned and strong from a lifetime of farmwork. He smiles proudly as he stands with his wife, Sreylin*, in the garden of their home, overlooking his extensive field of crops. Behind them, their grandson Chantha plays with his two cousins and his biological brother, all of whom now live with Leap and Sreylin.

The family dynamic is cohesive and organic. However, Leap admits he had some reservations when DT staff first approached him about possibly having Chantha come to live with them.

“As a farmer, I spend a lot of my days away from the house in the field so initially I was worried about what would happen to Chantha and how he would care for himself when I was away. What if he needed to use the toilet, what if he needed help? How would he do these things without me?” Leap recalls.

DT staff, well aware of the intricacies of family reintegration especially with CWD, devised a multi-step plan that would allow Chantha to visit his family in stages, spending more time with them each visit with the goal that he would ultimately go to live with them permanently.

DT social workers provided instructions to Leap and his wife about caring for a child with a disability; however, they quickly came to realize Chantha was more than capable of caring for himself.

“During the first few times Chantha came to visit us, I kind of tested him a little,” Leap says. “I would ask him to bring me certain things or help his grandmother with a few tasks. Each time, he would respond with ‘Let me do it!’ and I understood that he wasn’t going to be a burden at all. In fact, he actually relieves a lot of our burden because he can help take care of his younger cousins.”

New School Brings Opportunity

It was not just his family that were impressed by his capabilities but his teachers as well. Access to education is a major component in DT’s reintegration strategy but Leap was concerned how Chantha would attend the public school and if they would be able to cope with his disability. During one of the initial visits to Chantha’s grandparents, DT social workers also visited the school to educate the principal and teachers about having a student with a disability in the classroom. As with Leap, they were at first apprehensive due to their lack of experience with disability and concerns about Chantha’s safety.

When asked about the challenges of having Chantha in her class his teacher, Thang Khao, says, “Really, there are no challenges. I realized very quickly that he can do the same tasks as all of the other students so it has been very easy to adapt.”

She is the only grade 1 teacher for the school and has been with them for 7 years. “I am really impressed by what a great student he is,” she says fondly. “He is so focused on his studies. When it is time for break, the other students rush out the door, but not Chantha. I am very impressed by his discipline: he always finishes his work before leaving. I was also surprised by how talkative he is! He is never afraid to share his ideas.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Chantha’s natural charisma and sociability has made it quite easy for him to make friends. Even though they were initially told to be cautious when playing with Chantha so as not to injure him, the children now all engage in the same kind of rough-housing as 6-year olds do. One of the visitors from DT gathers the excited students together and asks, “Who asked to be Chantha’s friend first?” At once, all of the hands shoot up along with a chorus of, “ME!”

Sokhim*, the school’s principal, is incredibly proud of his school because of its adaptability to having Chantha studying there. “For me,” he says, “I was the same as everyone else at first: worried about his safety and his ability to handle basic hygiene, like using the toilet. But then I realized, these are the same concerns we have for all children his age and we use the same precautions for the other students that we do with Chantha.”

Sokhim sees this as the first stepping stone to his school becoming known for its inclusion of children with disabilities and hopes it will encourage the neighborhood to send more CWD here. “I think that our teachers are capable of handling more CWD in their classrooms. We just need better infrastructure to accommodate the needs of CWD and our teachers need more training for coping with different types of disabilities.”

Adjusting to the Future

Regardless of what the future holds for the school, it looks bright for Chantha. “I love living here,” he says, playfully distracted, typical of a 6-year-old after lunchtime. “I like playing with my friends and helping my family in the garden and going to school. When I grow up, I want to be a soldier so I can catch the thieves that steal police cars!”

“Chantha, where did you learn about thieves stealing police cars?” Leap asks.

“I just know,” Chantha casually replies. “I know a whole lot about almost everything.”

Leap is still concerned about Chantha’s future. Not about how he will cope with his disability but more about Leap’s own ageing and what it will mean for the family’s financial stability in the future. “I worry that as I get older and cannot work as much, we won’t have money for Chantha to continue his education,” he says woefully. “I see a lot of potential in him and want him to continue his studies until at least Grade 12, ideally continuing through university.” For now, though, he tries not to think about the future and just enjoys the added liveliness of Chantha’s presence: another laugh, another happy voice, another family member in their home.

*Names have been changed to protect their identities.